Designing Networks

Use this section to help decide if a network is an appropriate approach for your program’s context or to help create a network that is appropriate for the achieving your goals.

What is a network?

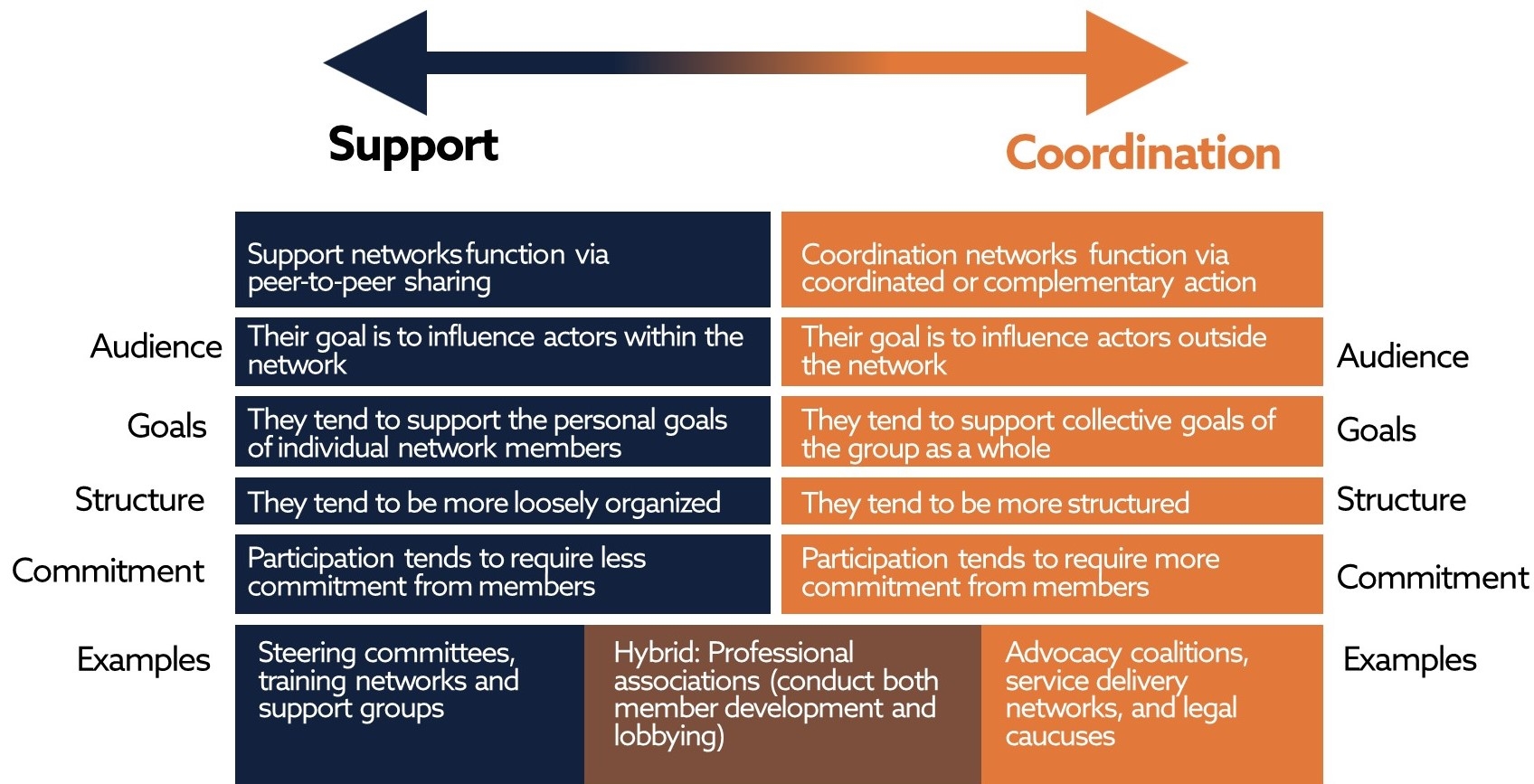

We define a network as a group of individuals or organizations that pursue a shared objective and interact with each other on an ongoing basis. A network implies some notion of reciprocal exchange between members, such as information, social capital, personal time, etc. Networks exist on a continuum based on the degree to which the network goal is providing support to members as opposed to coordinating action:

To use a metaphor, think about support networks like a swim team. The support of the team matters and there is an aggregate score, but races are won by individuals or small groups. In contrast, coordination networks are more like a basketball team, where winning happens collectively as a group.

In the DRG space, a support network might focus on something like building professional skill sets. A coordination network might focus on something like advocating for new laws. Many networks act as hybrids and do a bit of both. Regardless of where it falls on the continuum, a key feature of a network is that purposeful, ongoing interaction coordinated by members (not implementers) must be fundamental to its existence. (This is a little different than how a network might be defined to a social scientist, but it helps us define our terms in a programming context more effectively).

Why should you care?

Maybe you have read this far and are not certain why distinctions between the different types of networks really matter. However, network types determine network goals, and network goals contribute to important decisions about your program’s activities and measures of success. For more, please see the Implementing Networks and Measuring Networks sections.

Note: More often than not, networks will not fall perfectly on one side of this continuum or another, but our research has found that a key characteristic of successful network programming is maintaining intentionality about what your network is focusing on and why. See the “Why Choose a Network” section below for more on which network you should choose and under what circumstances.

Also, do not overthink what your network calls itself. Cultural preferences, the degree to which civic space is open or closed, and a variety of other factors may impact the preferred terminology. This continuum is just intended as a guide to aid in project design and monitoring and evaluation efforts.

If this definition still feels a little abstract, check out one of these examples. Keep reading for additional context and guidance.

Why choose a network?

Networks can be a powerful way to build a sense of community, solidarity, or momentum toward a social goal, but they do not work in every context. Based on our research so far, networks thrive when a combination of the following conditions exist (though no guidance is universal, and conditions may evolve over time based on staff feedback, evaluation research, and other new evidence):

There is an incentive for network members to be connected. These incentives could include access to things that members could not get on their own, such as:

Peer support and “safety in numbers.” This is especially true for marginalized groups, people working on sensitive topics, or those working in closed spaces who may feel isolated or powerless on their own. For more on the value of networks in closed and closing spaces, see this resource.

Specialized skill sets. This is especially true for people working on collective goals for which their individual skill set is insufficient to achieve the objective. (For example, a coordination network made up of human rights advocates might benefit from the addition of a few legal experts to help proofread their policy proposals against existing laws, or communications experts to make sure their message is appealing.)

There is sufficient social trust for network members to meaningfully share information or collaborate, or you believe that you can build that social trust during the project lifecycle. Generally, the evidence shows that the outcome of coordinated action is strongly dependent on the existence of trust between individuals because it lowers transaction costs. This can be a challenge for networks that aim to incorporate members of opposing political parties, or political parties and CSOs, unless there is pre-existing momentum and incentives for these groups to coordinate.

Previous studies promote capitalizing on existing trust (e.g., personal connections) of network members. You might consider leveraging specific individuals who are in the best position to reach out, mobilize, or identify sub-groups for the network.

Multiple actors are already working on the topic of the intended network. If a nascent network already exists, all the better. Previous evidence suggestions that networks that have materialized as a result of “a pull” (i.e., self-organized) are more likely to persist and more pragmatic overall. Regardless of what network you work with, try to diagnose what that network needs and support it rather than creating a new one.

There is a trusted organization or individual who can serve as a network facilitator, especially if the network you want to support is more focused on collective goals.

Previous studies emphasize the need for a facilitator and other persons to manage the network. Their roles could include connecting actors to and within the network, creating spaces for debate and internal collaboration, or convening stakeholders. In contexts with large, long-term coordination networks, having dedicated staff who can plan, manage, and support projects is ideal.

Examples of network project goals:

Journalists create a safe space to share strategies to oppose government misinformation

Local activists work together to write a new policy and advocate for it to become a law

Note: If your goal is strictly to build capacity, a network might not be a useful addition to your project. Maintaining the structure and cohesion of a network requires a lot of work, which might not be worth it unless you are explicitly trying to help a group of actors to learn from each other or coordinate to achieve a shared goal.

These conditions are good indicators that a network in general might be a good program approach, but what about the choice to select a support network vs. a coordination network, or a pre-existing network vs. building a new group from scratch? Click here for more strategies on building and supporting networks.

What is not a network?

Many DRG programs aim to increase the capacity of a group of actors and provide them with the opportunity to share lessons, connections, and encouragement. Quite a few DRG programs have the additional goal of wanting groups of actors working on similar issues to work together to achieve a goal. However, these conditions alone are not sufficient to select a network as your program approach or to define your project as a network.

Recall the definition: A network is a group of individuals or organizations that pursue a shared objective and interact with each other on an ongoing basis. Both the shared goal and the ongoing interaction are critical.

For example, a series of trainings provided by an implementer to a group of CSOs is not a network because there is no expectation of reciprocal exchange between members. Although these CSOs might have a shared goal of increased knowledge on a particular subject, they don’t have ongoing interaction because they are attending the training series to receive knowledge from the implementer, not from each other.

This training series could supplement a support network if the program included activities and goals around these trainees working together on homework assignments or conducting follow up social events with one another. This training series could supplement a coordination network if the program included activities and goals around these trainees working together to advocate collectively for a social change.

Note: Networks can develop unintentionally. For example, perhaps the attendees of a group training series decide to stay in touch and collaborate. That’s great! However, we do not cover these kinds of organic or unintentional networks in this field guide because you probably will not be developing activities and indicators around a result that you are not actively trying to contribute to. However, looking for the development of networks as an unintended result of a project is always a good idea!

Basic Network Results Chain

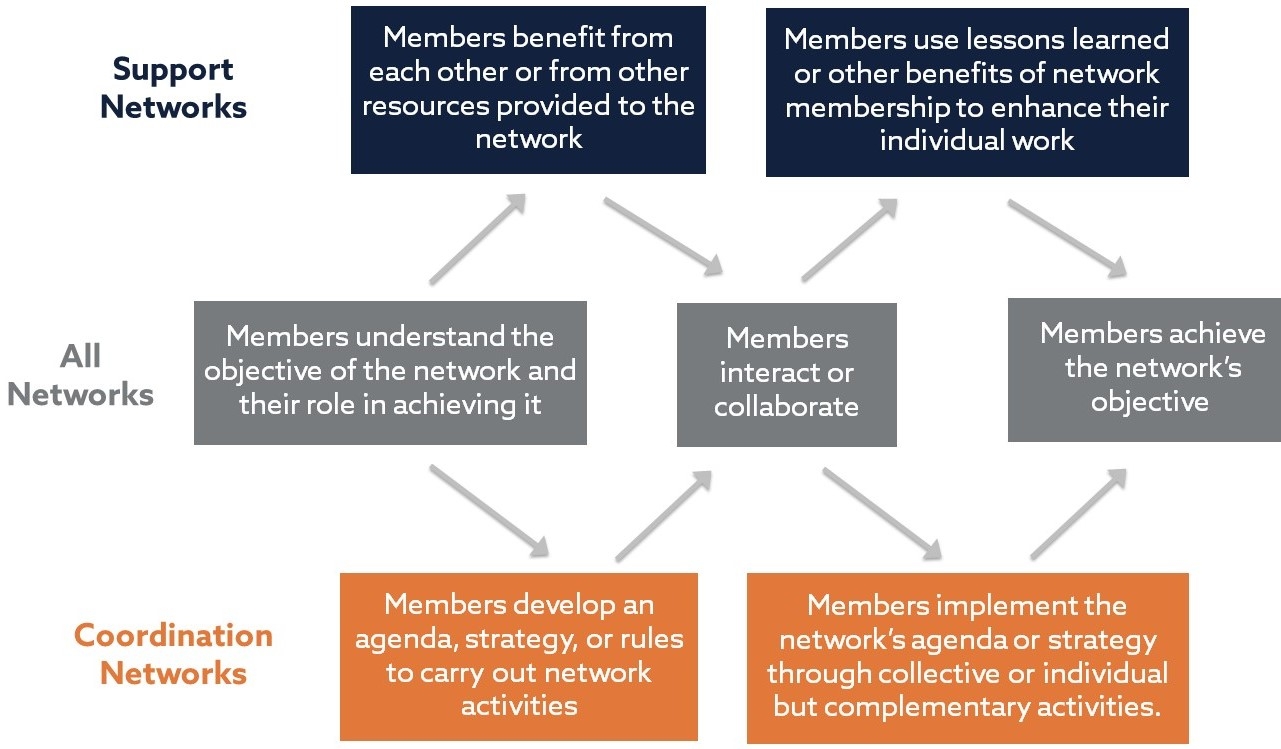

Networks apply diverse activities and tactics, so there is no universal results chain that applies every time. However, there are a few fundamental activities and results that are essential to network programming. In the visual below, you can see three key streams of activities and results. These streams are pictured together because most networks will probably contain some aspects of each stream. For more about the specifics of these activities and results, such as models for advocacy and organizational strategy, check out Appendix F.

Blue boxes are the activities and results that are most commonly seen in Support Networks, because they are focused on how networks influence personal goals.

Orange boxes are the activities and results that are most commonly seen in Coordination networks, because they are focused on how networks influence collective goals.

Grey boxes are the activities and results that are essential to All Networks.

If this definition still feels a little abstract, check out the examples in Appendix A.

Last updated