Appendix F: Models of Advocacy

The section outlines the pros and cons of several organizational strategies you might consider in your network-based programming.

Building networks and organizations based on organizational strategy

One challenge to successful advocacy is deciding how to collaborate as an organization or network. Even if they share a common goal, members of groups like these may have varying ideas of what a successful advocacy strategy should look like. Should the strategy be big and bold – capitalizing on media attention and lots of people to demonstrate mass approval? Or should it be subtle and targeted – drawing on political connections and research to quietly influence key decision makers?

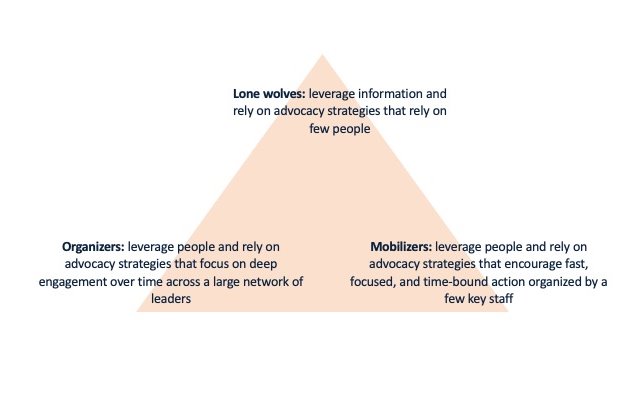

To help answer this question, political scientist Hahrie Han developed a typology of strategies that organizations use to engage their members and build power to influence change.

Han focuses on how mixtures of these three typologies affect organizational strategies in terms of how they engage members, allies, and volunteers. Lone wolves build power by leveraging information (e.g. meetings with decision-makers, policy and legal briefs, op-eds, and research). This group does not attempt to build a large membership and instead tend toward advocacy strategies that only rely on a few people and centralize responsibility within a small group.

Organizers build power by leveraging people. This group focuses on developing the motivation and capacity of their members to engage the public and they tend toward advocacy strategies that focus on deep engagement over time (e.g. through the creation of local branches or chapters of a national organization). They distribute responsibility to a large and often decentralized network of leaders.

Finally, Mobilizers also build power by leveraging people, but unlike organizers, they look to build a large membership that is available to take fast, focused, and time-bound action actions (e.g. signing petitions, attending rallies, etc.). Much like lone wolves, they centralize responsibility among a few key staff so these actions can be organized quickly.

This model does not argue that any specific typology is best, since effectiveness is determined by a number of factors, including the sensitivity of the topic, the degree of openness for civic activism, and the political opportunities available to activists, and other contextual factors. What it does argue is that for an organization or network to be most effective, they should align their advocacy strategies with their organizational development approach. A lone wolf - style organization probably doesn’t have the infrastructure to hold a successful rally on a short timeline, and likewise, a group of mobilizers probably isn’t best placed to organize different branches or chapters to develop locally tailored objectives.

IRI has used this framework to evaluate a number of projects with civic advocacy components and has developed the following guidance to consider when determining organizational or network composition.

Most groups aren’t a perfect version of any of these typologies, so we have categorized these tradeoffs by major organizational development decisions, such as structure, engagement and size. That said, don’t be afraid to mix and match approaches based on your context – one of the most successful IRI projects we evaluated supported a civic coalition that functioned like Lone Wolves behind closed doors – meeting with government, creating legislation and legal briefs, writing op-eds, and generally using person-to-person influence to advocate for change. However, they acted like Mobilizers, touting the possibility of mass demonstrations and events. This potential for mobilization of larger groups of citizens likely made government decision-makers more receptive to targeted advocacy. Coalitions that combine separate groups with complementary resources and skill sets can be more effective than those that rely on one strategy alone!

Closing Space Specifics

Advocacy is more difficult in closed spaces and other contexts where coordinated action is suppressed. Repressive governments make collective action more difficult by increasing the costs of participation for each group member. Rather than simply sacrificing time and effort for group action, group members risk their freedom, safety, and lives to contribute to group goals. That said, even when organizations and networks can develop and thrive in such spaces, the kinds of outreach and advocacy that they can conduct may be limited, both by government repression and the viewpoints and capacities of network members.

While our leverage over the former is limited, the latter is something we can account for in our programming approach. For example, consider asking network members directly if they feel comfortable coordinating, communicating, and making decisions. In a recent evaluation of civic network building in one closed space, we found that network members were intrinsically skeptical of decision-making structures that are viewed as too top-down or “authoritarian.” Such organizational governance was seen as undemocratic because decision-making power is not equitable across the organization. These network members craved clarity and some degree of structure, but not hierarchy. For this reason, consider supporting structures that spread power out more evenly across the group, such as federated systems. Keep in mind that while you may start with an “unstructured” network, it may be possible to switch structures over time as trust is developed among members.

Depending on the risk associated with assembling to conduct joint advocacy activities, in some closed spaces network members may prefer an indirect approach to advocacy (i.e. raising awareness around less controversial issues, or framing advocacy requests in a manner that is seen as less confrontational to the government). Framing political issues in this manner may encourage networks with lower risk tolerance to work towards promoting human rights. It could also help protect the wellbeing of network members and reduce their burn out rate. To increase pressure on repressive governments and avoid the appearance of working with the government, an indirect approach in country could be paired with a more direct approach out-of-country. For instance, facilitators could mobilize out-of-country networks to put pressure on the government to address human rights violations. Though the literature on this issue is both large and divided on which combination of approaches is most effective, it is possible that a coordinated attempt to pressure a government to uphold human rights could prove effective in certain contexts. However, international pressure can only be as effective as the information provided by activists on the ground. The combination would protect the safety of those operating in-country while bringing attention to the information they are sharing in-country.

Last updated